Professor of Crop Physiology Peter Kettlewell has recently written a piece on finding motivation within research for the latest issue of Research Fortnight. Entitled Words to Work By, he offers advice on rationalising failure and combining research disciplines. You can read his article below.

Few researchers will ever get the chance to ask the world’s most successful scientists and scientific entrepreneurs for advice. Journalists, however, get this opportunity regularly, and I have always looked to their articles in the hope of making my research more successful.

During a recent office move, sorting through mounds of paperwork accumulated over 40 years, I came across a folder where I had stored magazine cuttings of these articles and highlighted seminal quotes. In hindsight, I saw that the quotes fell into two groups: advice that I used consciously and frequently, and advice that is harder to put into practice but may have influenced me unconsciously.

Rationalising failure

One quote I have often remembered is: “If every project you start succeeds, you’ve failed.”

I clipped this out of an interview with Roger Needham published in the Cambridge Alumni Magazine in 1997. Needham was a pro vice-chancellor at Cambridge, a former head of the university’s computer laboratory and a pioneer in cybersecurity.

He had just been appointed to direct the European branch of Microsoft Research, which was based at the university and funded with £50 million over five years. Needham said the advice was given to him by Nathan Myhrvold, who was chief technology officer at Microsoft and founder of Microsoft Research.

In essence, Myhrvold’s point was that you should expect most research ideas not to work. A 100 per cent success rate is a sign that you’ve not been imaginative enough—your projects will yield incremental, predictable advances, but not a big or unexpected breakthrough.

Like most researchers, I have had a mix of successes and failures. The latter can be depressing, but when a project hasn’t worked as expected, thinking back to this quote has helped me to rationalise failures, to treat them as a learning experience and to maintain a positive attitude.

The same sentiment also helps when part of a research project fails—such as when a funder turns down a grant application, a journal rejects a paper or a technique for taking measurements doesn’t work.

Combining disciplines

Harder advice to put into practice is: “Major discoveries sometimes (perhaps often) occur at the fertile boundaries between established disciplines.”

This quote comes from John Krebs, writing in the Natural Environment Research Council’s magazine in the late 1990s. Krebs, NERC’s chief executive at that time, has followed his own advice, combining animal behaviour and neuroscience to show a link between bird feeding behaviour and brain anatomy.

Krebs’s sentiment is now widely recognised by funders. But the difficulty with putting it into action is finding a collaborator in a different discipline willing to step outside their comfort zone.

It is not easy to establish a rapport—at a conference, say—with someone with whom you share little common ground. Similarly, cold-calling potential interdisciplinary collaborators tends to be dispiritingly fruitless. But when I reflect on my past projects, the one that generated the most media attention—and has been cited across a wide range of disciplines—definitely adhered to this advice.

As a crop physiologist seeking to understand how crops were affected by the climate, I became interested in the North Atlantic Oscillation, a climate phenomenon with a powerful influence on Europe. This led me to an article by David Stephenson, a statistical climatologist, that showed an uncommon breadth of thinking. I sent him an unsolicited email and, for once, struck gold.

David was an expert on the NAO. Together, we sold our project to industry funders, who could see the potential of using an understanding of the NAO to predict crop performance.

Combining our knowledge, we developed a statistical model showing how the winter NAO could affect wheat performance several months later. This led to a method for forecasting wheat harvests based on winter weather, and later a technique for long-range forecasting of summer rainfall in the UK.

I had expected crop scientists and climatologists to cite the work, but it has also been referenced by archaeologists and medical scientists.

Achieving the impossible

I am still collecting quotes, although in a Word document rather than by taking scissors to paper. One of my more recent finds comes from an interview with the telecommunications entrepreneur Candace Johnson in Times Higher Education in 2017. It inspires me almost every day to overcome obstacles in any aspect of life or work: “When people tell me something is not possible…I think there must be a way to do this, and there always is.”

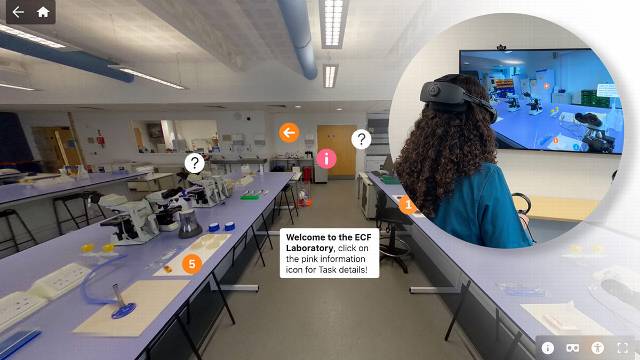

Blog: Veterinary Medicine students step into immersive 360° laboratory

At Harper & Keele Veterinary School, students are stepping beyond the traditional microbiology bench and into an immersive 360° labo …

Posted

Yesterday

Blog: Veterinary Medicine students step into immersive 360° laboratory

At Harper & Keele Veterinary School, students are stepping beyond the traditional microbiology bench and into an immersive 360° labo …

Posted

Yesterday