Earlier this week, Professor David Christian Rose, the Elizabeth Creak Chair in Sustainable Agri-Food Systems, was one of the speakers at a Westminster Forum online conference.

At the conference – which discussed Next Steps for Gene Edited Foods in England - he argued that its overwhelmingly ‘techno-optimist’ line-up at the conference didn’t speak for everyone.

His talk is below – and if you want to hear more of his thoughts on technology, he is one of the speakers on the Make the Difference stage at this weekend’s Future Fest – where he will be exploring whether tech will make a Field of Dreams – or Nightmares.

I want to start by addressing the elephant in the room – that most people speaking today, as is so often the case in debates around agricultural innovation, are overwhelmingly techo-optimists.

I, too, am frequently struck by the significant potential of emergent agricultural technologies to make things better for people, production, and the planet.

Today, the bias means we have many speakers from biotechnology-related disciplines who will put forward a positive vision of gene editing. But, of course, we do not live in a technocracy. Since we instead live in a democracy, I am going to ask us to consider not just what gene editing ‘could’ do for us, but what it ‘should’ do – what is gene editing for? Who is it for? And who should decide what the future of gene editing looks like in England?

Using AI as a tool to generate visions of future farming, I asked Dall-E 3 to generate images of future farms where gene editing technology is used.

I used contrasting key words, some to convey what I think are positive visions of future farming and some to articulate what I would not like. I recognise that the choice of keywords is a personal one – others would use different words, and others may have some of the ‘positive’ words on the ‘negative’ side and vice versa.

Though some may think that such an exercise is trivial, it does help to focus our minds on articulating visions of future farming that society may want to see.

Do we want to take heed of the plentiful research from the social sciences highlighting that emergent agricultural innovations, including gene editing, create winners and losers? Or that they have the potential to reduce farmer autonomy further in a corporate food system where distribution of inputs and outputs is controlled by the few? Or that innovation may help to sustain some models of agricultural production which have been bad for our environment?

That leads me to this article by Mario Caccamo, one of the speakers today. In this article, like many others on agri-tech, it is argued that food systems are not broken, that we need more innovation, faster, in order to feed a rapidly growing population and better protect our environment. In similar articles, those who may critique this framing of agricultural innovation are sometimes cast as being anti-scientific or morally repugnant because they would seek to raise questions of those silver bullets promising to eradicate food insecurity and environmental degradation.

Now, if we frame agri-food system challenges, as we commonly do in the UK, as immediate problems which can be solved by increasing yields, then we rush to ‘sanitize’ or re-brand agricultural innovation . We end up doing tokenistic consultations which ignore what publics say, for example, about labelling gene edited produce.

Our focus is on going fast, on producing more, and thinking about the consequences later. These are steps towards technocracy.

But, I would politely question, as many others have, whether our food system across the UK is working for the three million+ people who rely on food banks each year, or for the 800,000 people in 2022-3 who were admitted to hospital due to malnutrition or for the nearly two out of three of us who are overweight or obese and overwhelming our NHS because of it. Or, whether it is working for our rivers, air, or farmland biodiversity, or indeed for our food producers who feel unfairly compensated for their hard toil. Or, indeed, from a global perspective whether food systems work for the 700 million people round the world who live on the poverty line, many of whom live in countries where plentiful food is created, but where it is unevenly distributed and consumed.

This leads me to my overarching point. We have a fantastic opportunity with emergent agricultural innovations, including gene editing, not to do more, faster – but to do different, better. New technology could help transform agri-food systems towards fundamentally more sustainable models, rather than simply tweaking the status quo.

As the report by A Bigger Conversation shows, agroecological farmers, not always part of conversations like this one in which farmers as a heterogeneous group are represented by few representatives, are not anti-technology. The same is true of members of the public, so well-articulated by the Nuffield Council on Bioethics in their report into gene editing in livestock.

Rather, if we include a diverse range of stakeholder views beyond the usual suspects, we end up with very considered assessments of the role, if any, of gene editing in our food system. This enables us to develop better policies that go beyond a narrow focus on how we can have gene editing faster; but rather ask how policy instruments can ensure that gene editing and/or alternative solutions benefit all people, all of the environment, and all those involved in producing food.

Ultimately, we need to get better at asking not just what gene editing ‘can’ do’ for us, but what it ‘should’ do.

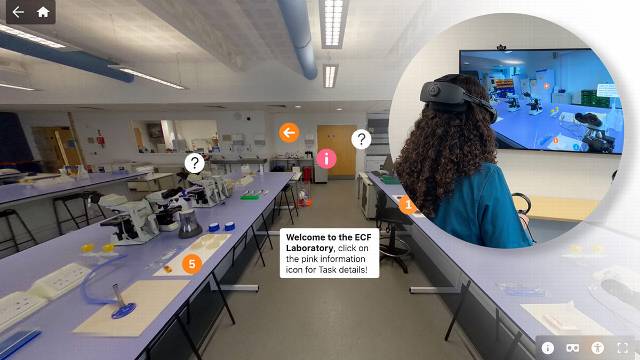

Blog: Veterinary Medicine students step into immersive 360° laboratory

At Harper & Keele Veterinary School, students are stepping beyond the traditional microbiology bench and into an immersive 360° labo …

Posted

Yesterday

Blog: Veterinary Medicine students step into immersive 360° laboratory

At Harper & Keele Veterinary School, students are stepping beyond the traditional microbiology bench and into an immersive 360° labo …

Posted

Yesterday